Zugzwang in Chess (with illustrations/board examples)

Chess is created in a way that a player has to move during his/her turn without having the opportunity to pass. You have to make a move even when the only moves possible are bad moves.

Having the turn is not always desirable, as there are situations where every move is a bad one but you have to make a move anyway. This is what is known as a “zugzwang” position.

Zugzwang (German for “compulsion to move”, pronounced [ˈtsuːktsvaŋ]) is a tactic usually implemented in chess and other turn-based games where a player is obligated to move even at the cost of their position.

In other words, it is a situation where every possible move that can be applied by the player will greatly harm their chances of success.

If you are new to chess, chances are you’ve never heard of this concept. Trust me, it is much easierto understand than it sounds. This article will explain everything with some illustration and pictures.

Without further ado, let’s get started.

The Zugzwang

This is actually a rare scenario that is usually encountered in textbooks and puzzles rather than on-board games, which speaks about their commonality.

However, they do happen and is the basis for some of the most common endgame principles such as the opposition and triangulation.

So it’s very important for a player to be equipped with the knowledge since they will still be faced with the situation even if not common.

There are two types of zugzwang, the squeeze and the mutual.

Common Zugzwang (Squeeze)

The most abundant type of zugzwang; only one player would be at a disadvantage if it’s their turn to move.

Simply means that one of the players will still have available moves that would not risk their respective position.

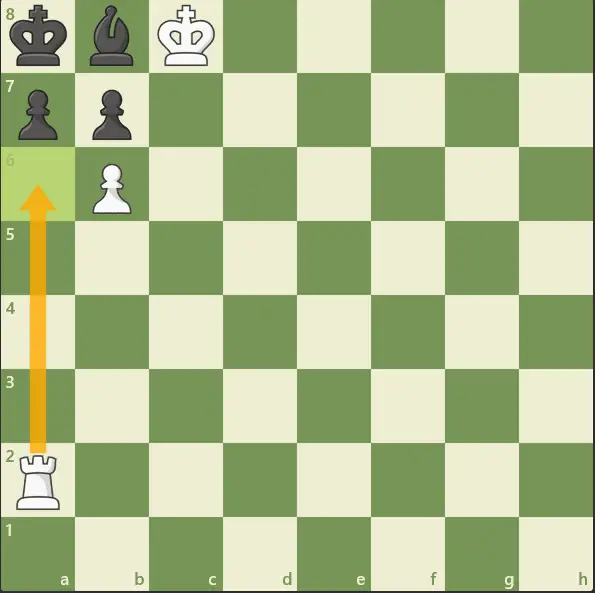

Look at the picture below composed by Paul Morphy (unofficial world champion) in 1840:

Let’s say that white played rook to a6:

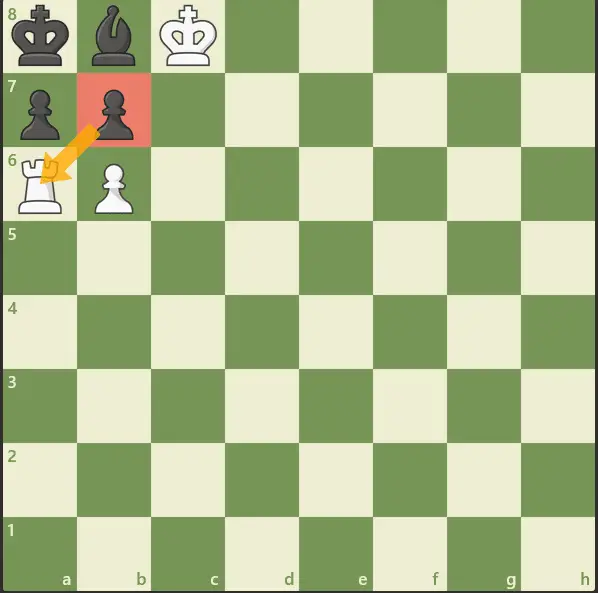

Black is in a Zugzwang! Every move to be played is a losing one.

If pawn takes rook a checkmate will occur:

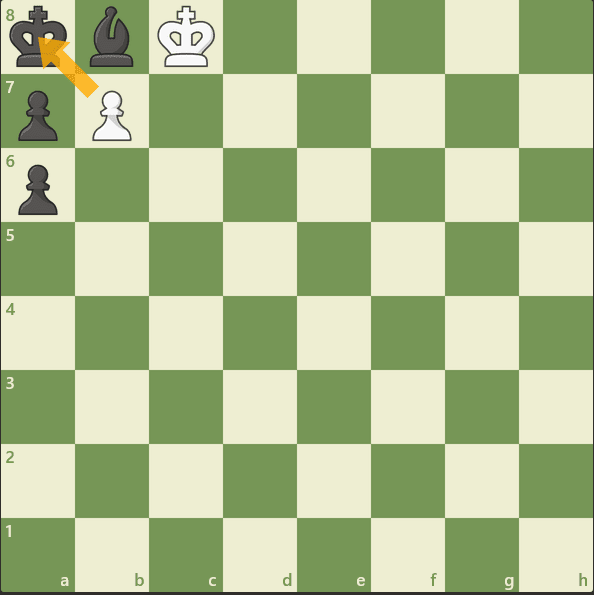

If the bishop moves anywhere, the rook can mate:

So back in that position, black would’ve been better of by just not moving at all! the checkmate wouldn’t have been possible.

But black had to move, and enter what’s described as zugzwang.

That is actually an example of a common zugzwang (squeeze), but an in-game demonstration might be better even if the one above qualifies.

Here is the famous match between Bobby Fisher (Future World Champion) and Mark Taimanov.

Fischer vs. Taimanov Game 2

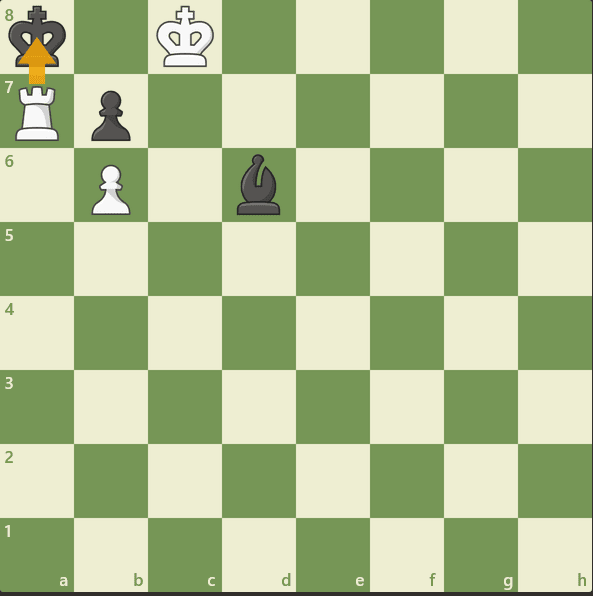

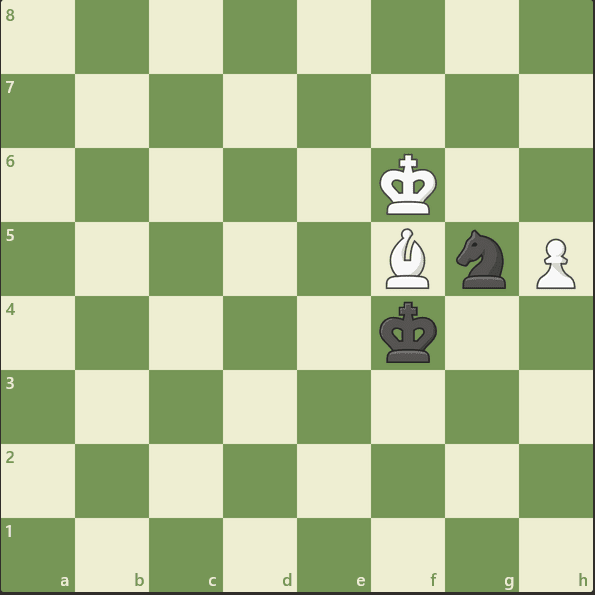

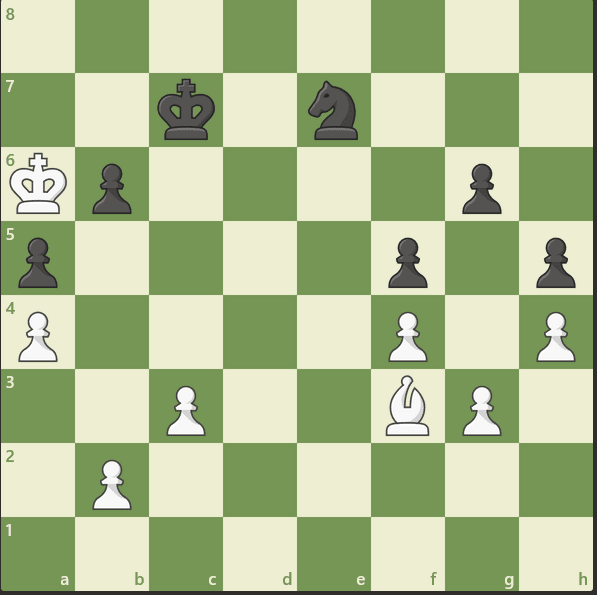

In this game Fisher is white and Taimanov is black which you can see below:

This is considered as a zugzwang for black since there aren’t any remaining moves that would save the position.

However, this is not a zugzwang for white since there are still moves to be played that would not risk its position, unlike Black.

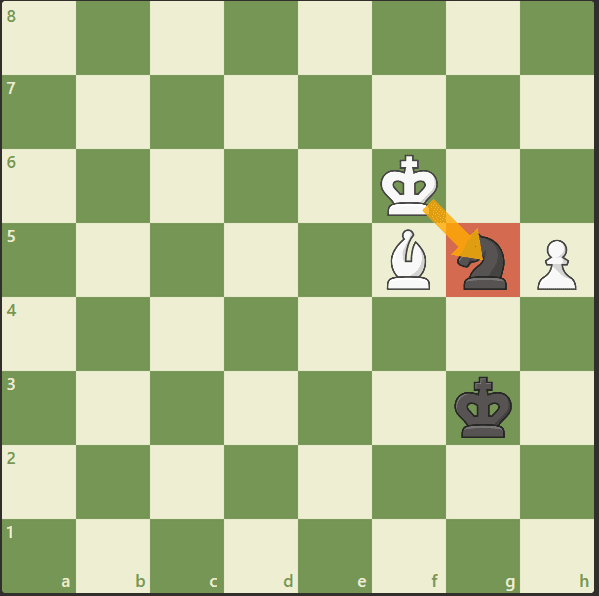

At that position, if the king moves the Knight would hang:

Is the knight moves the pawn will advance (to promotion) with little chances of counterplay:

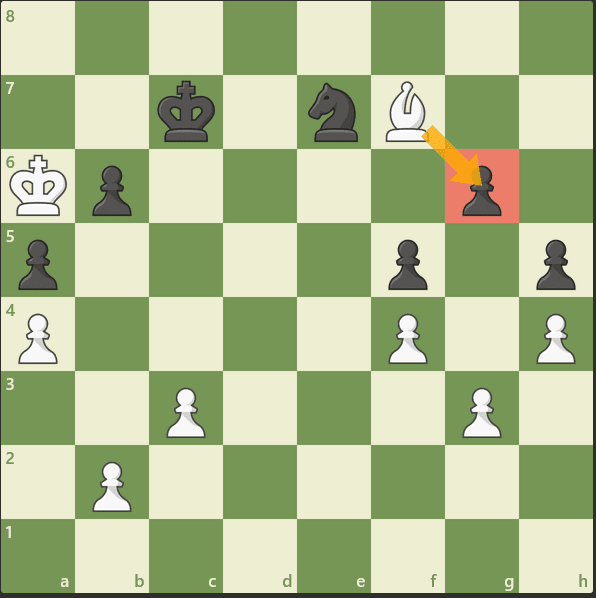

Which is exactly what happened!

The game continues as the following:

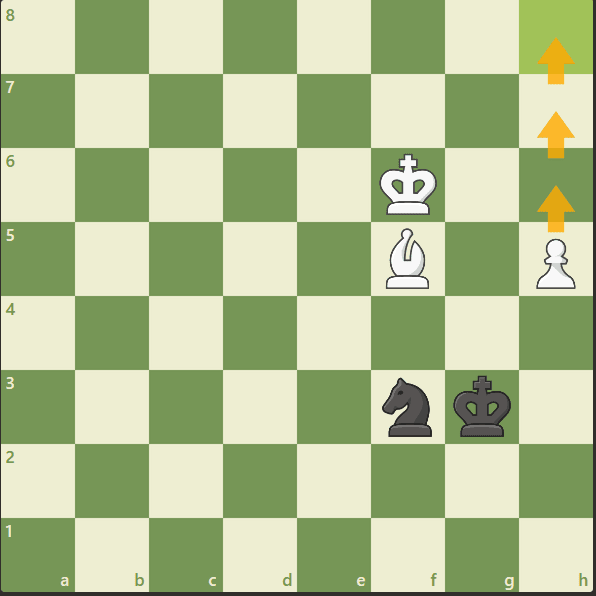

Another zugzwang for black! the position offers no possible move that could impede the pawn’s path of promotion.

Here’s how the rest of the game played out:

White won! with the power of zugzwang forces black to move into a losing endgame.

There’s actually another game from this exact same match-up where a zugzwang takes a key role:

Fischer vs. Taimanov Game 4

Fisher again has White while Taimanov has black with the following position:

The white king would really want to capture the base of the pawn chain defended by the black thing; the black king cannot move since the black pawn will fall.

The white bishop would now want to attack the other pawn from the kingside to put black in a zugzwang.

The game continues:

Now, look at this position:

White can now play a waiting move while still attacking the Kingside pawn, putting black in the Zugzwang!

Here:

Either the black king will move to allow the capture of the queenside pawns, or the Knight will move to allow the capture of the kingside pawns, a Zugzwang!

Taimanov chooses to move his King allowing the capture of his queenside pawns.

Here’s the rest of the game:

White eventually won since there are too many pawns for the black Knight to handle.

Now that’s done let’s talk about the other type, the mutual Zugzwang.

Mutual Zugzwang

A mutual zugzwang also known as reciprocal zugzwang is a position in chess where both players would lose the position if it’s their turn to move since there are no moves that would not cost them the game.

This is different from the common zugzwang (squeeze) where only one player is at risk from having no available moves.

These are the common samples of a mutual zugzwang:

Mined Squares

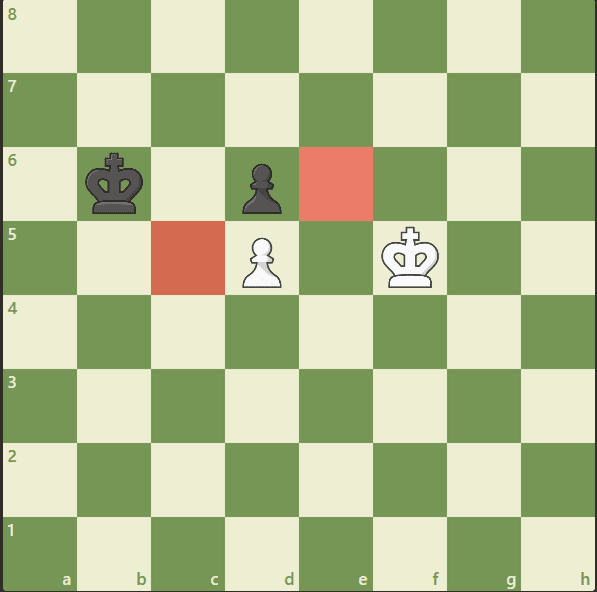

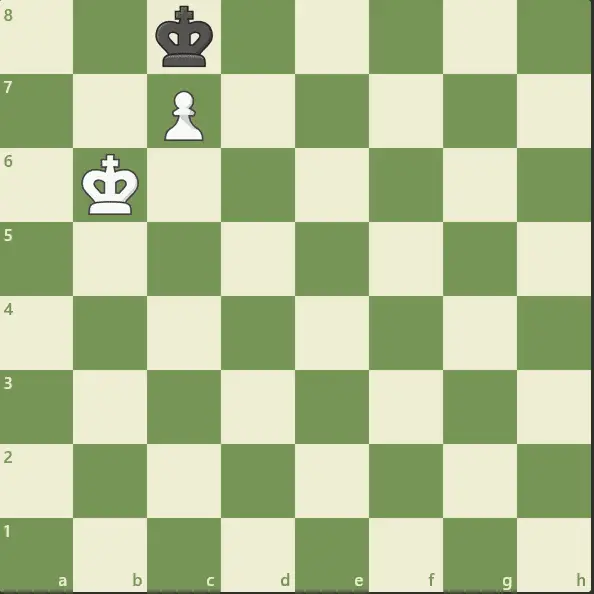

This is a common dance between kings only found in endgames which you can see below:

Both kings are not allowed to step in the mined squares (color red) since that will inevitably lead to a zugzwang.

Which you can see here:

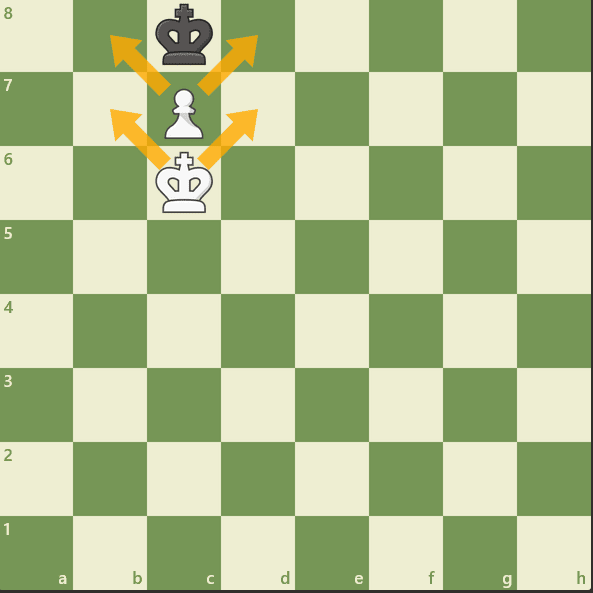

White stepped in the mined square during his turn, Black follows to enter a position known as a trebuçhet.

Whoever is to move in this position loses, and since white head in first, black can follow passing the turn to white.

The game unfolds as the following:

This is completely winning for black! The position could have been drawn if white avoided the mined square.

Reciprocal Pawn Promotion (Zugzwang)

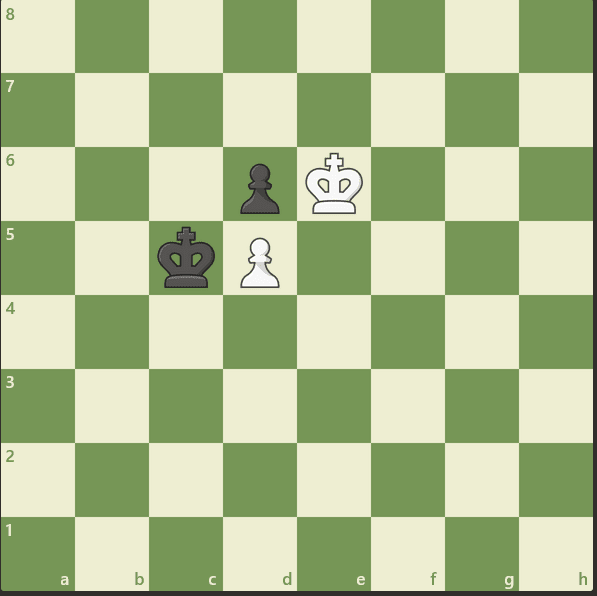

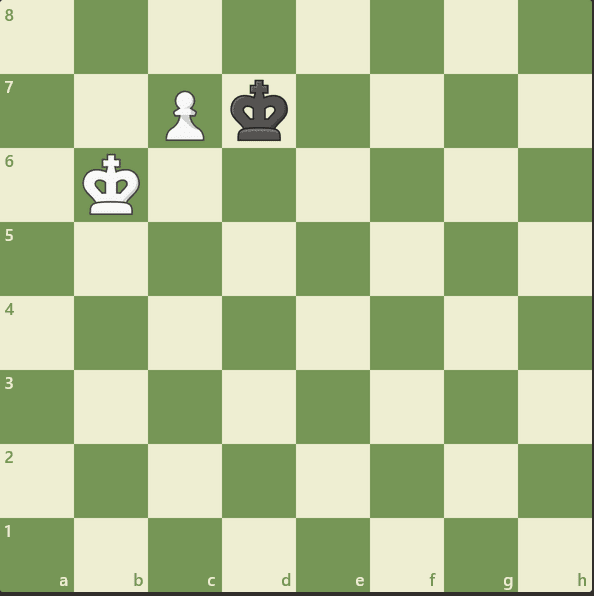

Another is this common pawn promotion position where if white is to move, then the position is drawn, and if black moves white will win.

Look below:

Let’s say white is to move here, either the king will move away from the pawn for it to be captured (which is a draw), or it’ll keep defending the pawn.

Like this:

Which is a stalemate! this is still a draw.

White is considered in a zugzwang since any move available harms its success (win), by only getting a draw.

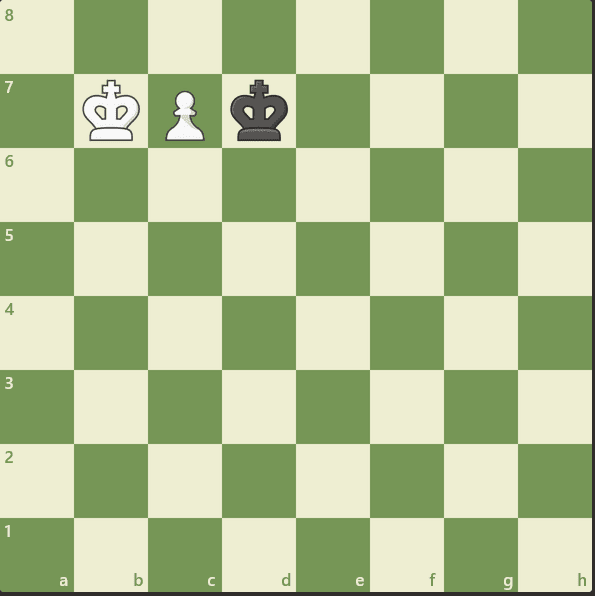

On the other hand, if black were to move well, there’s only ever one square of choice which you can see below:

Black is forced to move away from the promotional tile giving room for the white king to escort the pawn:

If black hadn’t moved from the last rank (row for pawn promotion) the pawn would’ve been blocked, sealing any chance for white to push.

Black is therefore in a zugzwang since it was forced to move in a way that would cause a losing game.

Zugzwang lite

This is a term perpetuated by Jonathan Rowson (chess player) which is not an actual

zugzwang, but runs on the same idea.

First let’s define a zugzwang, it is a situation where the extra move forces one side to

significantly weaken their position.

In zugzwang lite the extra move still brings concessions, but not as decisive as a zugzwang where it’ll immediately end the game.

Like this game:

Portisch vs. Tal

Strong player Portisch (White) faces Mikhail Tal (Magician of Riga) which is a perfect example of zugzwang lite.

This is the position:

The board is completely symmetrical but Tal believed he had a significant advantage being the second one to move.

He expressed that by moving second, he can have a better idea of white’s move and decide whether to copy it.

This is a zugzwang lite since there isn’t anything decisive for one side wanting to get rid of their “move”, but is just annoying that makes it harder to play.

In other words the zugzwang lite refers to the big picture rather than the small one.

Final thoughts

Being able to move in chess is a privilege that grants us the opportunity to accomplish our goals.

This is both a blessing and a curse since there are positions that we’d rather not play any move, but still have to anyway.

Seeing a zugzwang in real life is like an art, beautiful and worthy of praise.

Sleep well and play chess.